On March 9, 2017, North City Water District’s Manager Diane Pottinger, PE joined members of the Washington State Association of Sewer and Water Districts (WASWD) in Washington, DC, where they met with 10 of our state’s 13 congressional delegation and representatives of the National Water and Sewer Industry Associations.

The purpose of their visit was to discuss the potential loss of two significant funding sources for water and sewer infrastructure improvements—Washington State’s Public Works Assistance Account (PWAA), and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—and explore what funding alternatives might exist.

Update as of Tuesday March 21:

The Senate’s proposed budget summary released today recommends the PWAA’s revenues be permanently redirected into the Education Legacy Trust Account. “Additionally, $127 million in the 2017-2019 biennium and $20 million in the 2019-2012 biennium are assumed to be from the loan repayment sources.” Read the proposed operating budget here >

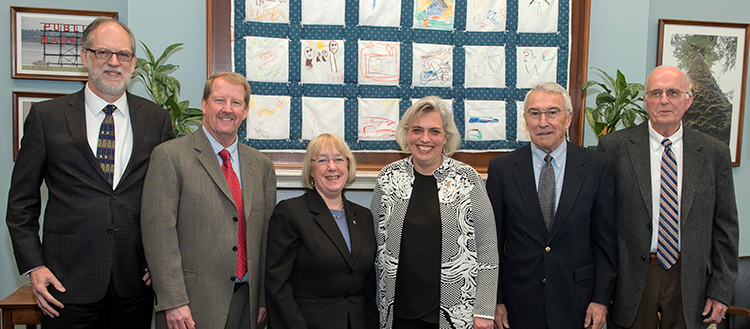

Pictured above from left to right: Jeff Clarke, General Manager of Alderwood Water and Sewer District; Jim Kuntz, Executive Director of WASWD; Senator Patty Murray; Diane Pottinger, PE, District Manager of North City Water District and Board Member of Washington State Public Works Board; Tom Agnew, Board President of Liberty Lake Sewer and Water District; Brian Egan, President of Washington Association of Sewer and Water Districts (WASWD) and Vice President / Commissioner of East Wenatchee Water District

Pictured above from left to right: Jeff Clarke, General Manager of Alderwood Water and Sewer District; Jim Kuntz, Executive Director of WASWD; Senator Patty Murray; Diane Pottinger, PE, District Manager of North City Water District and Board Member of Washington State Public Works Board; Tom Agnew, Board President of Liberty Lake Sewer and Water District; Brian Egan, President of Washington Association of Sewer and Water Districts (WASWD) and Vice President / Commissioner of East Wenatchee Water District

Critical Status of Infrastructure

Not only would the loss of these two funding sources have a directly negative impact on the cost of water and sewer service in our state, but it could not come at a worse time: the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) just today released their sobering 2017 National Infrastructure Report Card. Most of us are familiar with what happened in Flint, Michigan, but few realize those types of infrastructure problems are not isolated.

Water and sewer infrastructure provides a critical foundation for our society. Why are they so often overlooked? Underground systems are invisible… and a lot easier to ignore. Cities would sooner include more visible transportation projects in their annual infrastructure planning—even though a water system technically “transports” water to and from our schools, residences and businesses.

With Representative Dan Newhouse (4th District)

With Representative Dan Newhouse (4th District)

Infrastructure Funding Sources at Risk

Washington State’s Public Works Assistance Account (PWAA)

Established in 1985, our state’s Public Works Assistance Account (PWAA) has been an extraordinarily successful infrastructure funding program within Washington state.

The PWAA is managed by Governor-appointed members of the Public Works Board, in accordance with Revised Code of Washington (RCW) 43.155. From its initial seed money of $35 million, along with a small percentage of annual real estate excise tax, solid waste tax, and water and sewer tax, the fund is able to provide extremely low interest financing to help small and large cities, special purpose districts, and public utility agencies proactively upgrade and replace aging water and sewer infrastructure.

Over its 31 year history, the PWAA has loaned $2.8 billion dollars for projects totaling $4.6 billion in Washington state construction, resulting in the creation of more than 46,000 jobs. Not one of these loans has ever defaulted.

PWAA funding provides loans for six different types of infrastructure systems, including sewer, water, stormwater, roads, bridges, and solid waste; however the majority of their loans are applied to water and sewer infrastructure:

- Water: $107 million (35%) in 2012; $62 million (49%) in 2013.

- Sanitary Sewer: $147 million (47%) in 2012 and $60 million (47%) in 2013.

With 86% of PWAA loans (totaling $375 million) dedicated to these types of infrastructure improvements in Washington state, the PWAA is critical to maintaining the quality and safety of our state’s drinking water and sanitary sewer system.

However, Washington state legislators are considering permanently eliminating the PWAA, and diverting all of the revenue that the program has generated (and is expected to generate for several years to come) into the Education Legacy Account to fund schools.

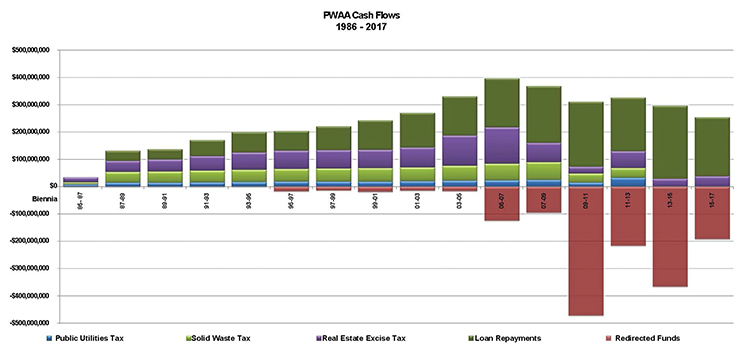

The following graph depicts how PWAA revenues have come in (blue = Public Utilities Tax; light green = Solid Waste Tax; purple = Real Estate Excise Tax; dark green = PWAA Loan Repayments); and how those revenues have been diverted by Washington state legislators to other non-infrastructure uses over the past several years (shown in red):

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

For decades, the EPA’s $8 billion annual budget has included several loan and grant programs for water and sewer infrastructure improvements at the local / state level.

Some of the more common sources of EPA funding include the State Revolving Fund (SRF) loan programs (which are also partially funded by the Public Works Trust Fund), the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (DWSRF), and the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CWSRF).

Unfortunately, grant funding is expected to remain frozen or reduced in 2018, as the White House considers reducing the EPA’s overall budget by 24%. Rumors of further reductions at the state level include a potential 30% reduction in both the drinking water grants and lead grants.

The Future of Water and Sewer Infrastructure Funding

As both our state and national governments begin to prepare their budgets, changes in infrastructure funding programs will most definitely have an impact on local water and sewer rates.

Without access to low interest loans from PWTF and EPA, special purpose water and sewer districts must fund their capital improvement projects with bonds—where interest rates are currently over 4%, and can be unpredictable from year to year. Higher bond financing costs must then be passed on to the rate payers in the form of higher rates. How much higher?

Case in Point:

Clark Regional Wastewater District received a $20 million loan from the PWAA for their $29 million Discovery Corridor Wastewater Transmission System project in Southwest Washington state. Had they financed this project through bonds, District General Manager John Peterson estimates it would have cost $11.4 million more—in terms of funding costs as well as the administrative costs associated with issuing sewer revenue bonds. Says Mr. Peterson, “The PWAA funding process is both financially and administratively efficient.”

Meanwhile cities and counties can either go out for bond financing, or they have the unique option of levying an additional tax on top of water and sewer rates, which once again is passed on to the rate payer. However this tax may be diverted to the general fund rather than reinvested into the water or sewer system.

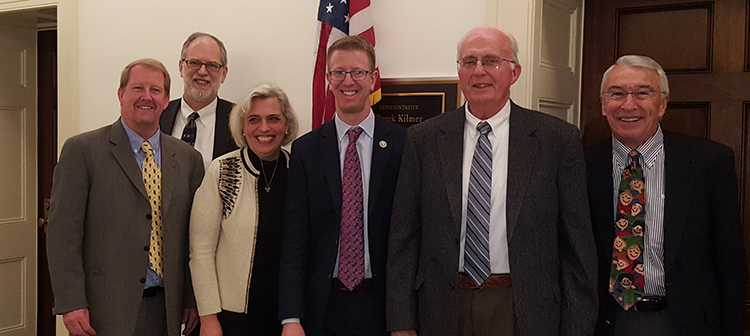

With Representative Derek Kilmer (6th District)

With Representative Derek Kilmer (6th District)

In President Trump’s inauguration speech, infrastructure was high on his list. What is still unknown is how he expects to address (and finance) these infrastructure needs.

Fortunately our Washington State Congressional Delegation are in ideal locations on different committees that can be helpful to our cause. In many meetings with our legislators, we’ve repeatedly heard that our Congressional delegation will be focused on resolving health care issues first, then tax reform, and likely later this year they will begin discussions regarding infrastructure.

Understandably, the water and sewer districts of Washington are ready and able to help solve the problem. From the smallest district that serves about 100 customers, to our largest that serves over 170,000 customers, we have always remained singularly focused on water and sewer service—we know how to do it well AND affordably.